Mud Lake, 1833

Father Pierre Charlevoix

The first historical mention of Chicago (in writing) can be found in a report written by Father Pierre Charlevoix in 1671; “Chicagou at the Lower End of Lake Michigan”. Father Charlevoix, a French Jesuit Priest, was also a historian and explorer. Some even say that he was a spy, reporting on the location of troops during the French & Indian War. None-the less, Charlevoix traveled widely, checking on the conditions at French Missions, making notes, mapping areas, and reporting back to the French government about his findings. Note, the priest never made it to Chicago, as his superiors directed him to travel to the Mississippi River, and though it may have shortened his journey, the route through Chicago was obstructed by tribal warfare.

Marquette & Jolliet

Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet

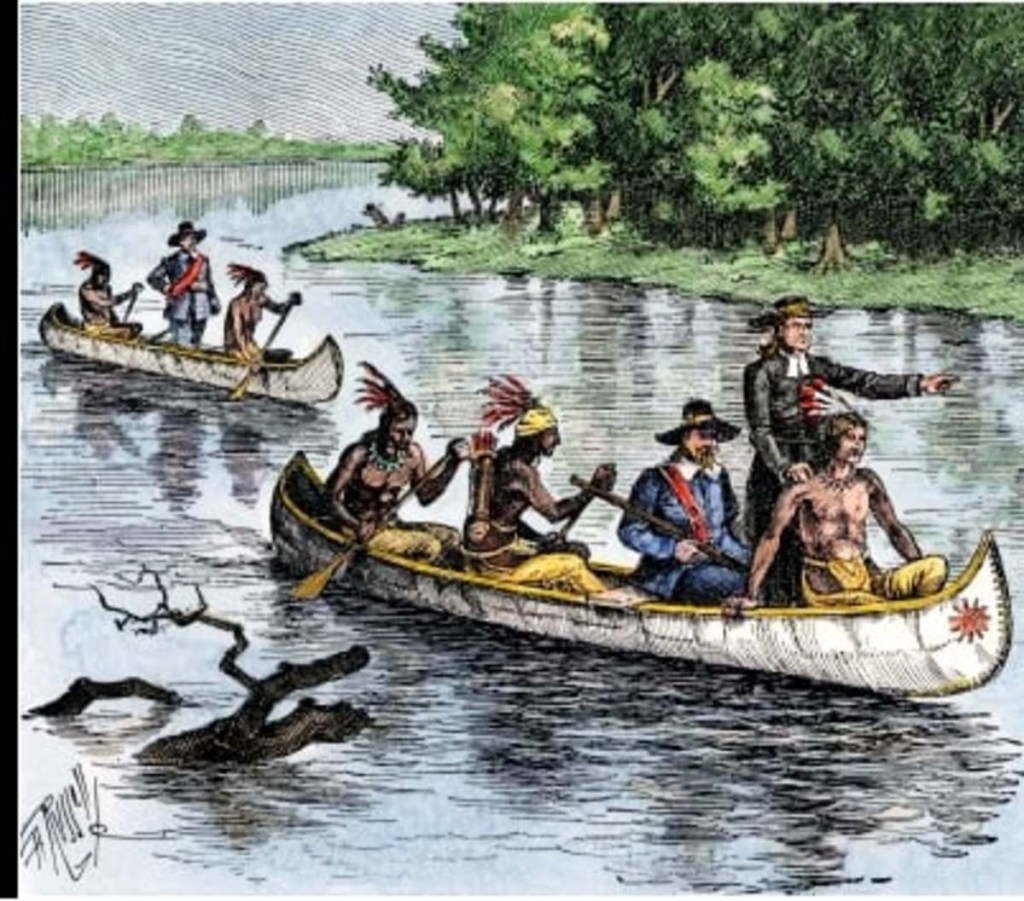

Two years later, in 1673, explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were exploring the Mississippi River, and during their travels, traveled past what would become the city of Chicago. In Joliet’s report he notes that a canal linking the Mississippi to Lake Michigan would serve to control the North American continent.

Marquette and Jolliet began their expedition in 1672 at the behest of Louis XIV. Louis XIV had received reports from French scouts that copper deposits had been found in the area around Lake Superior, and the king was determined to take advantage of their discovery. Moving copper ore, however, wasn’t as easy as transporting furs. Finding a new route was a necessity.

Jacques Marquette

Louis Jolliet

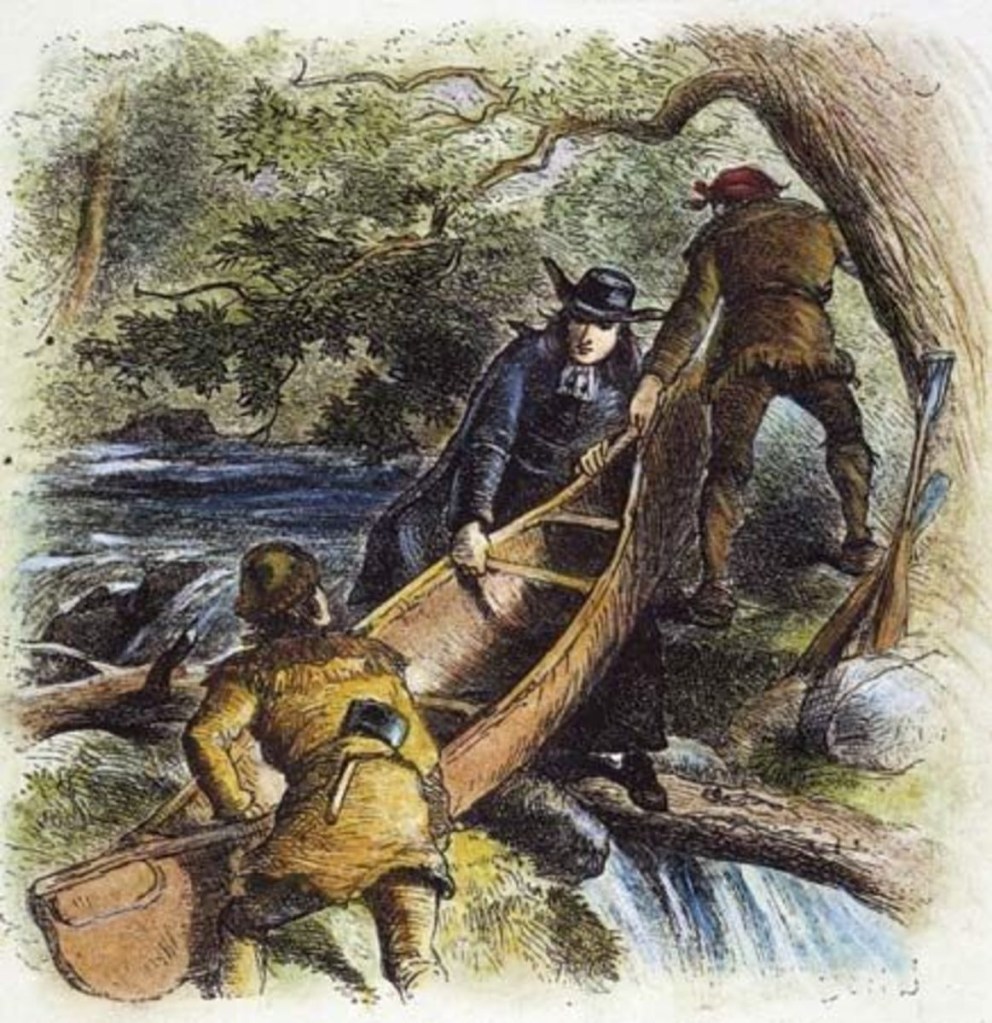

Mud Lake

Louis Jolliet was born in Quebec, the son of a wagon maker. At the age of ten he was sent to the Jesuit college to become a priest, and at the age of twenty-three he decided that the priesthood was not for him and left school to become a coureur des bois or woods-runner. Jolliet was put forth as head of the expedition by the Governor of Quebec, Frontenac, and Marquette was sent along as his spiritual guide.

The portage, which was shown to Marquette and Joliet by members of the Kaskaskia, had been in use for centuries. Surrounded by towering oak trees in an area that was home to beaver, otters, deer, black bears and other types of wildlife, the seven-mile bog later became known as Mud Lake. Shortly after, Jolliet and Marquette would become the first Europeans to traverse the pathway that would later become “The Chicago Portage.”

René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle

We now fast forward ten years to meet explorer, René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle. Like Jolliet, La Salle studied for the priesthood; unlike Jolliet, he took his vows in 1660, and five years later he requested to be sent abroad as a missionary. Within another two years, La Salle asked to be released from those vows on the basis of moral weakness. In March of 1667, the Church granted his request.

That same year, La Salle arrived in New France… without money or vocation. He did, however, arrive with a dream… finding a route to the Vermillion Sea (Pacific Ocean), which would in turn, would open up a new route to the Orient.

In 1679, Louis XIV ordered La Salle to take possession of the Mississippi Valley in his name. Along the way, La Salle arrived at the portage in 1682 writing, “This will be the gate of empire, this the seat of commerce.” Three months later, he would claim the area in and around the basin of the Mississippi River for France, its name… Louisiana.

René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle

Early Settlement

During the late 1600s, the settlement in what would become the great city of Chicago, served as a transit point… a place to rest, regroup, and resupply. This transit source would briefly pause, however, when the continuing wars between the French and the Fox Indians made access to the port impossible in the early 1700s, wars that would continue for a span of forty years. By the end of the French and Indian Wars in 1763, use of the port and increasing trade would boom, eventually leading to the construction of Fort Dearborn in 1803.

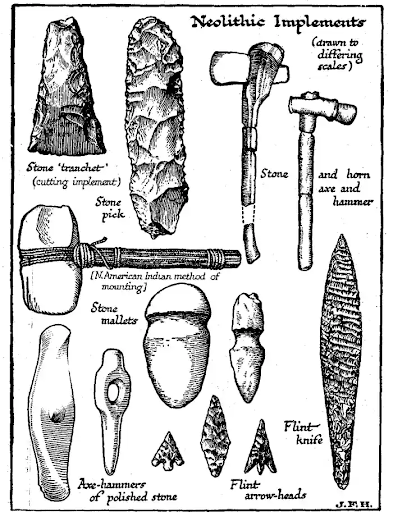

Prior to the fort’s construction, the fur trade was controlled by merchants from France, England, and Scotland, who used imported goods such as kettles, beads, alcohol, awls, and guns to exchange for furs supplied by the Native Americans and French Métis (French/ Native American lineage). The furs in demand during this period included bear, beaver, the black fox, deer, and otter.

The Fort Dearborn trading post, which also served as a factory, attracted skilled artisans. The construction of the fort, however, wasn’t merely a means to produce and trade, it was also a way to end the British monopoly of the fur business and to break the hold the British had over the region itself. The ability to do this was a direct result of the Treaty of Greenville (1795) in which the Pottawatomies, Miamis, and their allies gave up their rights to “one piece of land, six miles square, at the mouth of the Chicago River, emptying into the south-west end of Lake Michigan, where a fort formerly stood” to the United States.

Captain John Whistler

1803 & the Construction of the Stockade

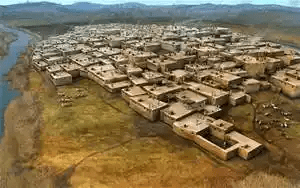

Captain John Whistler arrived in Chicago in the summer of 1803 to plan and oversee construction of the area that would become Fort Dearborn, named after Henry Dearborn, who served as President Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War. When completed, the fort which might be more aptly described as Chicago’s first settlement, housed soldiers, as well as their families, and was surrounded by homes and businesses.

Whistler’s son, William, who served under his father, would spend most of his service in the Fort Dearborn area, and two of his children were born within its palisades. Before arriving at the fort, the Whistlers were stationed in Detroit, and upon receiving their orders left Detroit and traveled overland under the guidance of Lieut. James S. Swearingen. Once Whistler’s group reached the Saint Joseph River, they embarked on a canoe for the final leg of their journey.

Fort Dearborn

Upon their arrival, Captain John Whistler immediately began preparations for the stockade that would shelter and protect his troops and family during the construction period. Mrs. Whistler noted that when they disembarked the canoe, “There were then here…. but four rude huts, or traders’ cabins, occupied by white men, Canadian French, with Indian wives.”

Captain Whistler oversaw the construction and completion of the stockade before the end of that same year. Construction, however, was no easy task. Without horses or oxen, the soldiers had no choice but to don harnesses and use ropes to lug the necessary timbers to the building site. The soldiers were responsible for every aspect of the project’s completion including cutting the timbers, hauling the wood, and providing the physical labor that was needed to erect the stockade itself. When it was completed, the real work began, and Fort Dearborn would eventually become a reality.

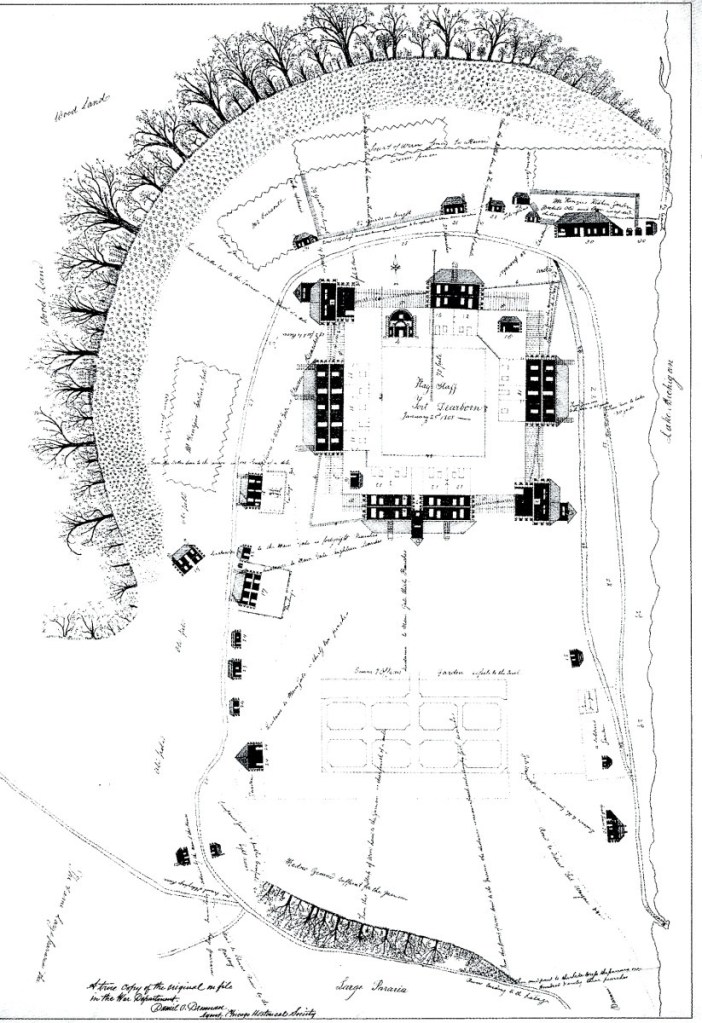

Five years later, in 1808, Fort Dearborn was completed. Located on the south bank of the Chicago River, the fort provided a base and home for American soldiers and their families, surrounded by homes and businesses. To the north, fur traders with Native American ties set up shop, most notably, John Kinzie, who’d purchased the home built by Jean Baptiste Point de Saible in 1804.

Plan of the first Fort Dearborn drawn by John Whistler in 1808

In 1810, Captain Whistler was called back to Detroit, and he was replaced by Captain Nathan Heald. Heald found the fort to be a place of isolation and loneliness, a feeling that was only changed by his marriage. In May of 1811, Heald and his new wife, Rebekah, arrived at the garrison… their new home, and according to historian, J. Seymour Currey:

“On their arrival the garrison turned out to receive them with military honors. Rebekah was much pleased with her reception, and found everything to her liking; she liked the wild place, the wild lake, and the wild Indians, then indeed friendly enough, but soon to become fierce enemies. Everything suited her ways and disposition, “being on the wild order” herself, she said; and we can well imagine Captain Heald becoming, in his changed circumstances, quite reconciled to the situation with which he was so much displeased the year before.”

Captain Heald is best remembered for being in charge of Fort Dearborn at the time of the Fort Dearborn Massacre in the year 1812. He is reputed to have been meticulous in his record keeping and disciplined in his actions, something he expected from his soldiers as well. Unfortunately, his men were used to a more relaxed atmosphere, and they resented his adherence to military regulations. Sadly, Heald’s adherence also interfered with his ability to take control of a situation that his superiors had no understanding of… his lack of independent thought and action is said to have contributed to the disaster that would eventually overcome the Fort and its inhabitants, but that’s a story for another day… a story soon to follow.

Rebekah Wells Heald

Fort Dearborn

1) Project Gutenberg’s The Story of Old Fort Dearborn, by J. Seymour Currey

Sources:

chicagology.com