Massacre at Fort Dearborn

University of Chicago

Looking Back

To recap my first installment, Mud Lake: The Future Home of Fort Dearborn, Captain Whistler, who planned and constructed the first real settlement at Fort Dearborn, was called back to Detroit in 1810. He was replaced by Captain Nathan Heald, who is best remembered for being in charge of Fort Dearborn at the time of the Fort Dearborn Massacre in the year 1812.

Captain Nathan Heald

Heald, reputed to have been meticulous in his record keeping and disciplined in his actions, expected no less from his men. Unfortunately, his men were used to a more relaxed atmosphere, and they resented Heald’s adherence to military regulations and lack of independent thought, something that can be seen in two ways. One, as a military officer he followed the orders of his superiors (or not), which is not only expected but required. Two, Heald doesn’t seem to have reached out to his superiors to question their plan (orders). If he was uncomfortable or unsure, why not voice that discomfort?

Sadly, Heald’s inability to make decisive plans that he would actually follow through ultimately interfered with his ability to take control of a situation that was his responsibility to control. His lack of independent thought and action contributed to the disaster that would eventually overcome the Fort and its inhabitants, and this is where we begin.

President James Madison

history.com

War…. again

The Fort Dearborn Massacre was preempted by the War of 1812, a three-year war between the Americans and the British…. a war that is often referred to as America’s “second war of independence,” a war that was officially declared by President Madison on June 18, 1812, a mere two months before Heald’s abandonment of Fort Dearborn.

So, what was everyone fighting for? America had won its independence from the British in 1776, but had it truly won its freedom? At the start of the 19th century, the British were involved in a longstanding war with Napoleon, and America became a pawn in their war, why? Well, that’s simple… let’s start with trade and supplies. Both France and England traded with America, and they both wanted trade with America limited to themselves. England and France both attempted to block America from trading with the other. England went so far as to require licensing for neutral countries that desired to trade with France or its colonies. England also engaged in impressment, the removal of American seamen from U.S. merchant vessels and forcing them to serve with the British forces.

In May of 1810, around the time that Heald took charge of Fort Dearborn, the United States Congress passed a bill that they believed would solve their problems with trade. The bill stated that if either Britain or France would drop their trade restrictions against the United States, the United States would in turn, stop trading with the other power. Napoleon implied that he would acquiesce. In response, President Madison blocked all trade with Britain.

Fast forward to 1811 and the Battle of Tippecanoe, a battle in which the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, who’d been rallying his people to resist white expansion planned an ambush on Governor Harrison’s troops the morning of what was supposed to be a scheduled council. It is important to note, however, that Harrison’s appearance in what would become central Indiana, was not intended to be a peaceful sojourn. His visit to Prophetstown,” named for Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa, “the Prophet,” was a military expedition. Its goal… to destroy Prophetstown, which had become the home base for the Native American confederacy.

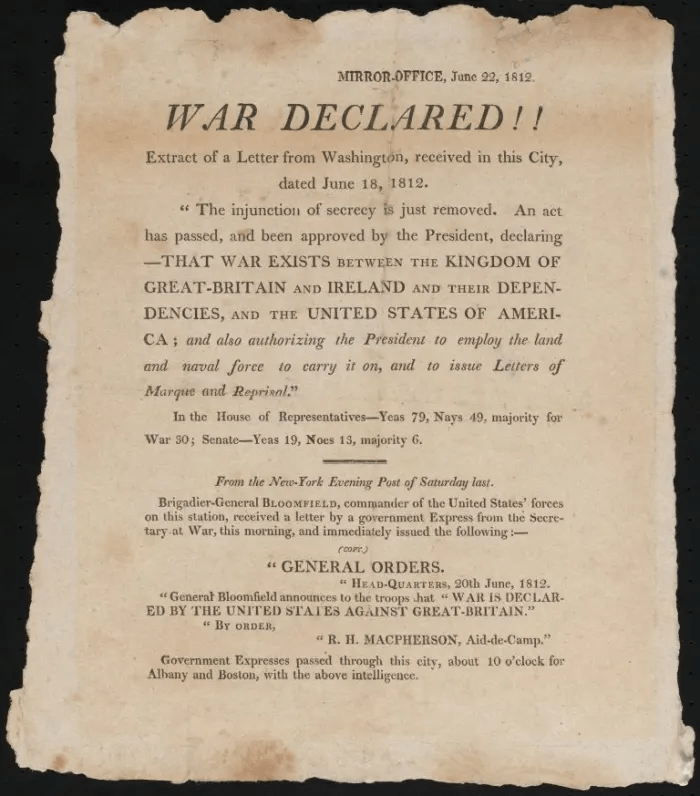

Declaration of War

USS Constitution Museum

Prophetstown

Harrison’s army was met by one of Tenskwatawa’s men, who carried a white flag and proceeded to relay Tecumseh’s desire for a ceasefire and subsequent parley with Harrison. Harrison agreed, and though he was skeptical, took his men to set up camp about a mile from Prophetstown, having no idea that Tecumseh was nowhere near Prophetstown. Tecumseh could not attend a parley… he wasn’t there. Tecumseh, in fact, had warned Tenskwatawa to refrain from attack, to refrain from inciting a war they were not yet prepared for. His brother didn’t listen.

Early the next morning, Tenskwatawa’s warriors surrounded Harrison’s encampment and breached their defenses. Harrison’s men, who were well trained and well prepared, defended their positions and after a few short hours forced the Native Americans to retreat. Harrison would later note the effectiveness of Tenskwatawa’s ambush and described it as “a monstrous carnage,” but not decisive. In the end, Harrison burned Prophetstown to the ground. His actions destroyed Tecumseh’s dream of establishing a Native American confederacy. In turn, they also cemented Tecumseh’s alliance with the British, an alliance that would play a major role in the British army’s success in the Great Lakes region during the War of 1812.

The Battle of Tippecanoe

William Hull

So, what really prompted the Native American alliance with the British? It wasn’t instantaneous, it wasn’t planned. It was something that grew over time. Possibly a result of misperceptions? Misunderstandings? Deceit? Lack of vision? Opinions are diverse, so let’s try and look at the facts.

Thomas Jefferson appointed William Hull as the first Governor of Michigan in 1805. Hull was a graduate of Yale, a celebrated war hero (the American Revolution), a lawyer, a judge, and a state senator all before accepting the position of governor. He was well qualified for the position, but yet, he had much to learn about walking a fine line between the Native Americans and the ever-expanding numbers of settlers moving into his territory.

Hull’s purpose as governor might seem to be simple: negotiate with the Native Americans and acquire land for settlement… peacefully. In some respects, Hull was successful. The Treaty of Detroit, for instance, annexed a large area around what would later become Toledo, Ohio from the Wyandot and Potawatomi nations. Unfortunately, the sheer number of settlers flocking into the area within a very short period of time angered the Native Americans, causing a resentment that would only grow in intensity. Enter Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh, two brothers who’d experienced war, the loss of family members, and regular relocation. Two members of the Shawnee, who’d seen their tribe slowly grow apart… brothers who were determined to reestablish and unite the tribes into one coalition. Some embraced the brothers’ ideals, others resented what they considered to be crossing tribal boundaries.

As time went on, the Native American resistance grew, a fact that led to Hull’s commission as Brigadier General during the War of 1812. Note, Hull was not a young man at the time of his commission… he was sixty years old, and for the most part, he’d led a comfortable life with all of the perks that accompanied his titles. His new appointment, however, was anything but “comfortable”. Tasked with heading a portion of the Ohio militia in the Invasion of Canada, Hull found himself in the midst of something he was ill prepared for and something that would tarnish his reputation amongst his contemporaries, as well as his place in history.

Governor William Hull

The Invasion of Canada

The Invasion of Canada was for all intents and purposes a complete train wreck, and Hull, at the head of the campaign, faced a monumental failure. Plans for the invasion were hurriedly laid out and executed without a backup plan. The militia itself lacked discipline and training, in addition to the fact that they were poorly supplied. In contrast, the British were ready and able to defend Canada. Assisted by the Native Americans and British intelligence, the British forces easily tracked Hull’s movements and gained access to his plans; they also captured a good portion of his supplies. The militia made it as far as Amherstburg before Hull decided that he didn’t have enough weaponry or naval support to complete his mission, a belief that led to his retreat to Fort Detroit and his eventual surrendering of the fort to the British. One of his officers is even recorded as having said, “He is a coward…and will not risk his person.”

On July 17, 1812, shortly after taking control of Fort Detroit, the British moved on to capture Fort Mackinac. Not a single shot was fired, and the fort, which had belonged to the Americans since 1796 was once again held by British and Native American forces. More importantly, this event marked the official starting point of the War of 1812 in the Great Lakes Region.

The Straits of Mackinac provided access to both Lake Huron and Lake Michigan, allowing the British to move quickly, as water travel was far quicker than moving over land, providing the British and Native American forces with something the United States had thrown away without a fight. Note, the garrison had not yet been informed of the United States declaration of war against Great Britain.

Due to Fort Mackinac’s location, it was an isolated post, and Lieutenant Porter Hanks of the U.S. Regiment of Artillery, who commanded the post only had sixty-one men in his garrison. Thus, when Hanks was apprised of the situation, he had to digest two important facts; his country was at war, and the fort for which he was responsible was the intended target of the 600 British soldiers, Native American warriors, and Canadian militia who lay in wait. Why Hanks, who had noticed large groups of Native Americans passing Mackinac Island and was said to have been suspicious, didn’t act on his suspicions is something we do not know. What we do know is that the British were gathering forces a mere forty miles away on St. Joseph Island, and that on July 16th they paddled their way to Mackinac, where they arrived at 3:00 am on July 17th… alerting no one.

Once the British, under the command of Captain Charles Roberts, had their cannon in place, and their men prepared for attack, Roberts sent Hanks a note asking for him to surrender the fort and warning him to do so in order “to save the effusion of blood, which must of necessity follow the attack of such Troops as I have under my Command.” Hanks complied.

Raising the White Flag at Fort Mackinac

hsmichigan.org

Orders Ignored

The surrender of Fort Mackinac almost immediately gave rise to what would be recorded in history as the Massacre at Fort Dearborn. Like Fort Mackinac, Fort Dearborn was a major location in the fur trade, it also provided access to Lake Michigan, which is derived from the Ojibwe word “mishigami,” meaning “large water” or “great water” and is the only one of the Great Lakes located fully within the borders of the United States.

Following the surrender of Fort Mackinac, orders were sent to Captain Heald to evacuate Fort Dearborn, as the United States military was worried about the ability to safely and efficiently transport supplies. Note, 300 miles separated the forts, thus Hull’s orders, which were delivered by Winamek, a Potawatomi leader, were slow in arriving. Hull’s orders were clear… all Americans were to provision themselves and evacuate the fort, all weaponry and ammunition was to be destroyed, and all remaining goods and provisions were to be distributed to the Native Americans who were considered allies. Hull also ordered that the evacuation was to take place immediately before anyone outside of the fort knew about their plans. Heald chose to ignore his orders.

Fort Dearborn, Display at the Chicago History Museum

August 14, 1812

Rather than follow the orders sent down by his superior, Heald called a meeting with the Potawatomi, and on August 14, 1812, almost one month to the day of Fort Mackinac’s surrender, Heald revealed his plans to the Potawatomi in detail, something that is best described in an article titled The Massacre of Fort Dearborn at Chicago published in 1899, in which, Potawatomi Chief Simon Pokagon, describes the event:

“To their surprise, he told them he intended to evacuate the fort the next day, August 15, 1812; that he would distribute the fire-arms, ammunition, provisions, whiskey, etc., among them; and that if they would send a band of Pottawatomies to escort them safely to Fort Wayne, he would there pay them a large sum of money.”

Almost immediately after, Heald went back on his word, promptly destroying the fort’s supply of both alcohol and ammunition. Believing that the whiskey would only rouse the anger of the Potawatomi, and that any gun powder or shot that was left behind might be used against them, Heald once again acted without thought. Unfortunately, the Potawatomi, who’d trusted Heald, felt that both Heald and the United States military were going back on their word. Local tribes were still battling over territory, and the Potawatomi, who’d lived somewhat peacefully since the fort’s inception, felt they’d been betrayed. With the desertion of the fort, the Potawatomi wanted to reclaim the area as their own, and in response to the military’s perceived faithlessness, Black Partridge, a Potawatomi leader, returned his peace medal to Heald that evening and issued a warning that Heald should take care when departing the next morning. His words, “I will not wear a token of peace,” he reportedly said, “while I am compelled to act as an enemy.”

Chief Simon Pokagon

The Massacre

The following morning, Captain William Wells, who was stationed at Fort Wayne, and who had rushed to Fort Dearborn after hearing of the evacuation, led the fifty-five soldiers, twelve civilian militia, nine women (including his niece Rebekah, Heald’s wife) and eighteen children away from the fort. The group traveled along the shoreline, never guessing that around 500 Potawatomi were hidden on the other side of the low dunes. When Captain Wells spotted the Native Americans and alerted the others that they were about to be attacked, Heald responded by ordering his troops to charge. The troops, rushing headlong over the dunes, were encircled by the Potawatomi that surrounded their flanks. Sadly, only twelve of the militia remained behind with the wagons… with the wives and the children, who were left open to attack.

Those twelve men fought desperately to save the women and children before being killed themselves. Muskets were fired and used to bludgeon their attackers, but twelve men against hundreds couldn’t save the children, who were traveling in the wagons. It is said that only one Potawatomi climbed into the wagon holding the children, and that one warrior was responsible for hacking them to death with a tomahawk. That warrior, reported Simon Pokagon “…. was hated by the tribe ever after.”

Within fifteen minutes the battle was over, as Heald agreed to parlay, and then to surrender. In return, the Potawatomi agreed to spare the remaining survivors. It is reported that sixty-seven people lost their lives that morning, a number that included Captain Wells, twenty-five soldiers, twelve militiamen, twelve children, and two women. Captain Wells’ niece, Rebekah, survived, and it is reported that her survival was the result of one man’s actions… Black Partridge.

Once Heald had surrendered, the group was taken back to the fort, where the badly wounded soldiers were tortured to death. Were these soldiers excluded from the agreement that the survivors would be spared? Were their deaths a part of the agreement? Or were they so near death that the Potawatomi simply did as they wished? This is something we’ll never know for sure.

What we do know is that in the end, Fort Dearborn was burned to the ground, that the survivors (captives) were divided up among the Native Americans and taken away, and that although most of the captives were ransomed and returned to their families, others were held for the duration of their lives.

As a result of the Great Chicago Fire, the majority of written manuscripts detailing the fall of Fort Dearborn were lost forever. From the information that remains, Captain Wells will forever be remembered as a hero. Heald, on the other hand, is remembered as nothing more than an inept fool. Is he deserving… I leave that answer to you.

The Massacre at Fort Dearborn

Sources:

michiganpublic.org

mackinacparks.com

potawatomi.org

Leave a comment