The Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War, like other wars throughout history, was not fought because of hatred and love for violence, but rather, for land. The US government wanted to expand its territory, and the Native Americans wished to retain their homeland. Treaties were signed, often peaceably, and yet, those same treaties were signed by individuals, who in some cases didn’t understand what they were signing… individuals who communicated the wrong information to their people.

That Black Hawk despised those who accommodated the government’s demands is without question. Keokuk became his enemy, their enmity reaching as far back as the War of 1812 when Black Hawk left his village to fight on behalf of the British, while Keokuk remained behind looking to usurp Black Hawk’s position amongst his people. Black Hawk would take up arms, whereas Keokuk was showered with gifts. Keokuk led his people down the road of concession, all while Black Hawk staunchly supported resistance.

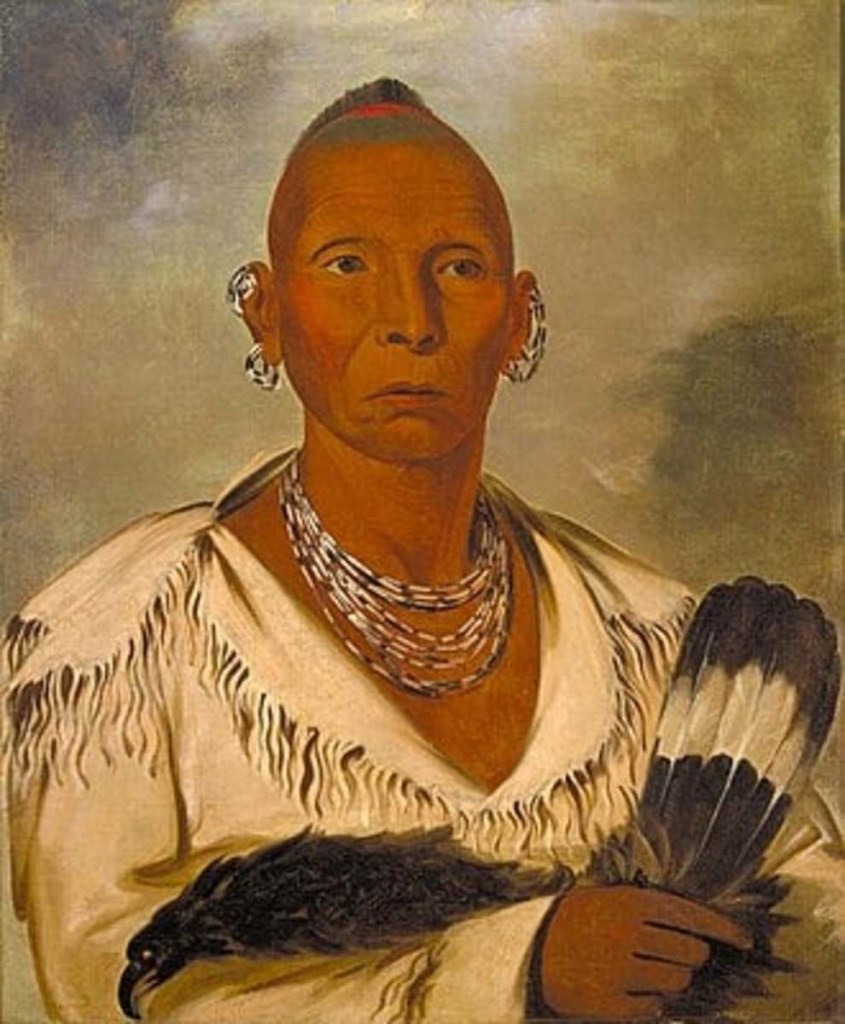

Black Hawk, Painting by George Catlin

The Treaty of 1804

Black Hawk’s participation in the War of 1812 was preempted by one important ideal, land ownership, something that Black Hawk did not believe in and refused to acknowledge. The Treaty of 1804, upon which the US government laid claim to fifty million acres of land was hotly contested by Black Hawk and his followers, who saw the treaty as invalid, something that was signed as a result of misunderstanding, miscommunication, or possibly, something that was pure and intended deception from the start.

Only five Native American leaders were present at the negotiations initiated by William Henry Harrison, the governor of the Indiana territory, and their presence in St. Louis had nothing to do with land. These representatives attended the discussions for one reason, and only one reason, the dispensation of justice and perusal of peace after an attack on settlers at the Cuivre River. The head men attended in order to pay retribution for the murder of three settlers, all men, who’d settled near the river illegally on Sauk land. As was the custom, the Native American leadership was prepared to offer compensation to the victims’ families, which if accepted, would settle the issue. Over and done… but it wasn’t.

During this meeting Governor Harrison would play negotiator, promising things he had no right to promise and bargaining with men, who according to custom, had no right to be sitting in attendance, let alone putting quill to paper. Legal treaties required protocol. Invitations to the Tribal Council were a necessity not a choice, tribal meetings attended by all members of the tribe were mandatory not voluntary. Every man, woman, and child of the tribe were to attend, and everyone played a role in deciding the amount of land to be negotiated, as well as the selling price. Note, if the women were not included, not informed, or opposed the sale, the treaty would be deemed invalid. None of these protocols were followed in the signing of the Treaty of 1804, supporting Black Hawk’s claims that the treaty was fraudulent.

Hope, Determination, and Betrayal

Between the years of 1830 and 1832, Black Hawk’s people crossed back and forth over the Mississippi River multiple times. In 1832, he returned to his homeland with what is said to have been one-thousand men, women, and children, carrying with them stores of seed. His followers, who represented the Sauk, Fox and Kickapoo tribes, fully intended to resettle in the area they’d left behind. The land dispute continued, and war would ensue.

Black Hawk, however, had no desire to wage war, and his decision to return was based upon promises of assistance by other Native American leaders. As additional militia arrived to assist Brigadier-General Atkinson at Rock Island, Black Hawk made it clear that he would not brook opposition to his people’s return. As Atkinson’s numbers grew, Black Hawk’s would diminish. Promises made to Black Hawk by White Cloud would be broken; he had no backing, no one would join him, and in response, Black Hawk knew that he had no other choice but to withdraw.

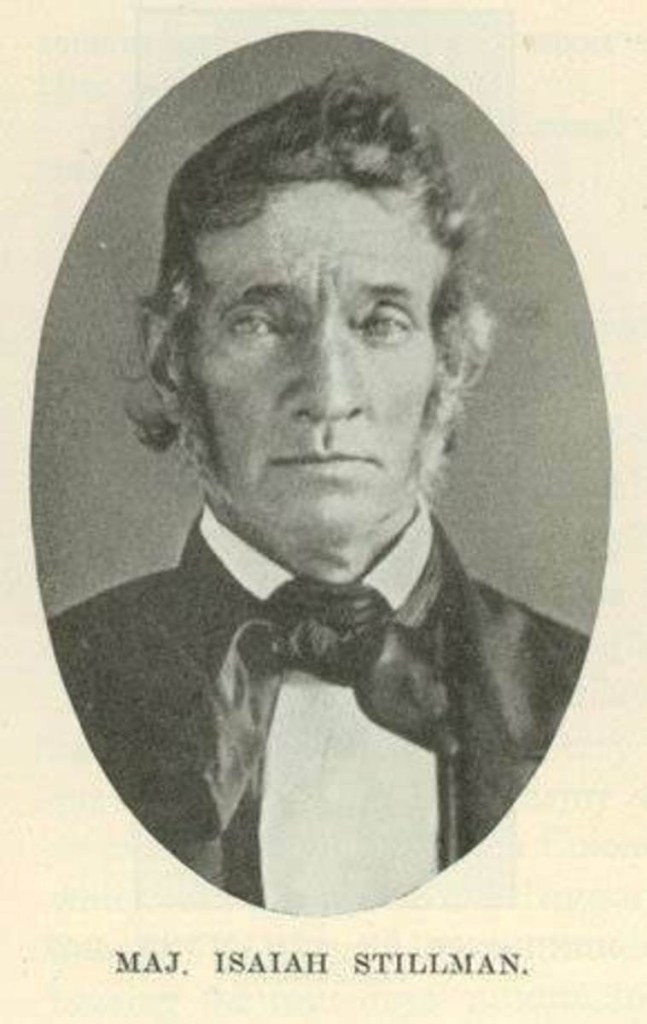

The Battle of Stillman’s Run

On May 14, 1832, Black Hawk’s tribe was in the midst of preparing for their journey back down the Rock River when they learned that Atkinson’s men were nearby. Black Hawk, who in his own words had already “resolved at once to send a flag of truce to Gen. Atkinson and ask permission to descend Rock river, re-cross the Mississippi and go back to their country….” then sent three of his warriors, carrying a white flag of truce, to arrange negotiations for their safe return. These negotiations never occurred, and the Battle of Stillman’s Run would ensue.

This battle would be a distinct loss for the US militia, but in the end, the US government had no intention of being defeated. Hence, the name it will be remembered by in history, the Battle of Stillman’s Run, is a tribute (or mark of shame) to Stillman’s panicked flight toward Dixon’s Ferry, and the many men who were initially listed as missing, but who had in reality run back to their homes. Even Black Hawk was amazed by the fact that so few warriors could defeat the attacking militia, but in the end, he knew that his dream for peace had come to an end. This knowledge led to his retreat, which was hastily set upon to ensure the safety of the elderly, the women, and the children, all for whom he was inherently responsible.

Black Hawk would take his people north, searching for food and sanctuary. According to Black Hawk, “This violation of a flag of truce, the wanton murder of its bearers, and the attack upon a mere remnant of Black Hawk’s band when suing for peace, precipitated a war that should have been avoided.” Sadly, he could no longer avoid the repercussions that would follow any more than he could avoid the militia that pursued him.

Apple River Fort Historical Site

The Battle of Apple River Fort

Black Hawk received no support from the other tribes, but then again, he did not expect it. White Cloud’s lies had placed Black Hawk in a precarious situation that left him biding his time. Well aware that he couldn’t hide forever, Black Hawk continued his trip north. During this time, skirmishes and attacks on white settlements would ensue. Small groups of warriors from other tribes would defy their leader’s pledges “to take no part in the war,” attacking settlements, taking hostages, and stealing horses.

In June of 1832, these rogue bands would keep the militia busy, all while Black Hawk continued moving. This isn’t to say that he didn’t participate. On June 23, 1832, Black Hawk and his warriors attacked Apple River Fort near Galena, and while the braves surrounded the fort, the militia, under command of Captain Stone, prepared their defenses. Every port hole was manned by a sharp-shooter, and while some of the women busied themselves melting lead for bullets, others conveyed those same bullets to the men during the hour-long battle. Aware that he couldn’t impregnate the fort without drawing a larger group of militaries, Black Hawk decided that pillage was his only choice, thus, he ordered his men to take whatever they could carry before removing themselves from the area.

Kellogg’s Grove Battle Site

Kellogg’s Grove

Rumors of sightings would lead the militia to Kellogg’s Grove, where Black Hawk’s men would attempt to ambush a group of soldiers as they departed the fort. The ambush was unsuccessful, an event that would lead to the pursuit of Black Hawk by Major John Dement and the soldiers under his command. Shortly thereafter, General Winfield Scott was ordered to travel with an additional eight hundred members of the U.S. Army via the Great Lakes to Chicago. His troops would never join Dement because of a cholera outbreak onboard the ship that would claim the lives of more than three-quarters of his troops.

On July 21, 1832, General James Henry and Colonel Henry Dodge would find evidence of Black Hawk’s tribe near the Wisconsin River. The evidence itself spoke to the condition of Black Hawk’s people. Pots, blankets, and other items littered the path on which they departed, hunger and exhaustion had forced them to lighten their loads in order to keep moving. Those who couldn’t keep up were left behind, dead or dying, and those who were dying were promptly killed by their pursuers.

Many of those who survived the initial flight were killed in battle or drowned while attempting to cross the river. Mirroring the violence attributed to the Native American warriors, Dodge and Henry’s men would take tokens from the battlefield, the scalps of nearly forty braves. Napope sought Dodge out early the next morning to attempt negotiations. Henry Dodge’s response, “Be assured that every possible exertion will Be made to destroy the Enemy crippled as they must be with their wounded and families as well as their want [lack] of provision supplies.”

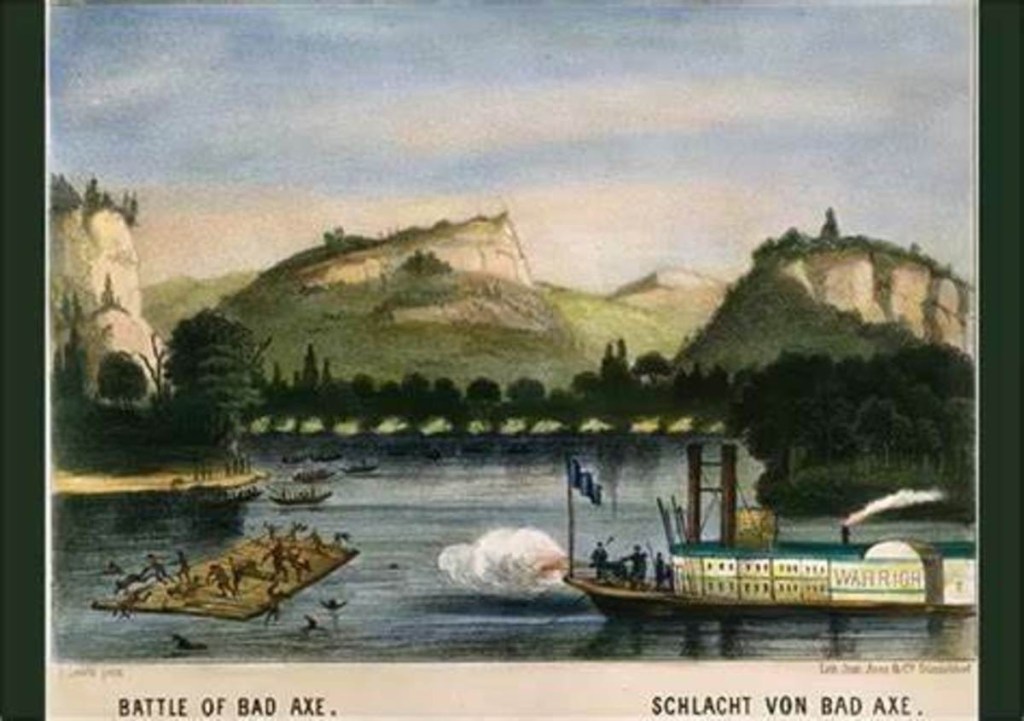

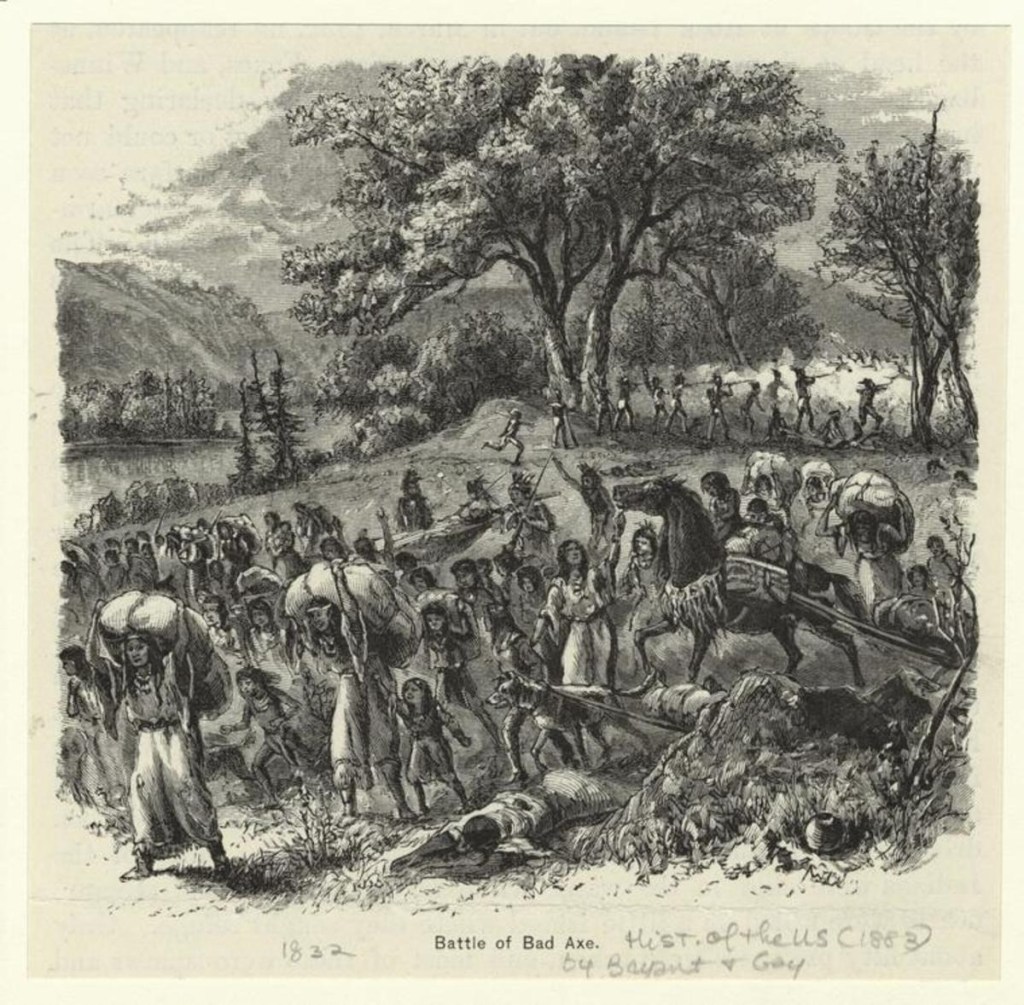

The Battle of Bad Axe

The disintegration of Black Hawk’s men wouldn’t deter the militia from achieving their purpose. His people, starving, exhausted, and without hope, would continue on their way toward the banks of the Mississippi, and the militia, well fed and well cared for would continue to follow. On August 1, 1832, Black Hawk and his people would arrive on the eastern bank of the Mighty Mississippi near Bad Axe, where a council would be held. Leaders present at the council advised breaking up the group and heading north in smaller bands. The people, however, disagreed and immediately began to construct rafts and canoes, some even managing to set off for the other side before the arrival of the Warrior, an armed steamboat that was returning from its mission to deliver a message to the Sioux.

The steamboat’s arrival changed everything. Faced with the arrival of the boat, artillery, and twenty soldiers, the attempts to evacuate were aborted. More importantly, Black Hawk would step forward once again to give himself up… to surrender for the good of his people, and once again his attempts would be misunderstood, ignored, or possibly both. What we know is that Black Hawk himself waded into the water carrying a white flag, as he tried to communicate with the soldiers manning the steamboat. It is well recorded that he remained there for ten to fifteen minutes, with his white flag raised, before the men on the ship, unprovoked, opened fire on the nearby Sauks and Foxes, killing at least twenty-five before the Warrior was forced to disengage and return downriver to refuel. For the third time, Black Hawk’s attempts to surrender had been ignored, and as noted in his autobiography, “After the boat started down the evening before, Black Hawk and a few of his people left for the lodge of a Winnebago friend, and gave himself up. Thus ended a bloody war which had been forced upon Black Hawk by Stillman’s troops violating a flag of truce, which was contrary to the rules of war of all civilized nations, and one that had always been respected by the Indians. And thus, by the treachery or ignorance of the Winnebago interpreter on board of the Warrior, it was brought to a close in the same ignoble way it commenced—disregarding a flag of truce—and by which Black Hawk lost more than half of his army. But in justice to Lieut. Kingsbury, who commanded the troops on the Warrior, and to his credit it must be said, that Black Hawk’s flag would have been respected if the Winnebago, who acted as his interpreter on the boat, had reported him correctly.”

The End of the War

The morning after Black Hawk’s attempted surrender, the Native American leader would once again find himself traveling northward, hoping to take refuge among the Ho-Chunk and Ojibwe, where he would officially surrender a few days later. Those who refused to accompany him faced another battle, waged or not waged against the troops that had gathered along the bluffs during the night to attack them from behind. Taking no prisoners seems to have been a priority for the militia, as anyone present on the shoreline was indiscriminately killed, men, women, and children. Later that morning, the Warrior would reappear firing its cannon at those who attempted to swim to safety. Those who made it to safety were summarily killed by the Sioux who were working with the Americans against their long-time enemies.

Although this battle ultimately marked the end of the war, the search continued. It would be almost a month before Black Hawk and White Cloud would officially surrender to the Winnebago agent, Joseph Street, at Prairie du Chien. Afterward, the Native Americans would be transported by steamboat to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis where they would remain for seven months before an official visit in Washington D.C. and their final journey to Fortress Monroe in Virginia.

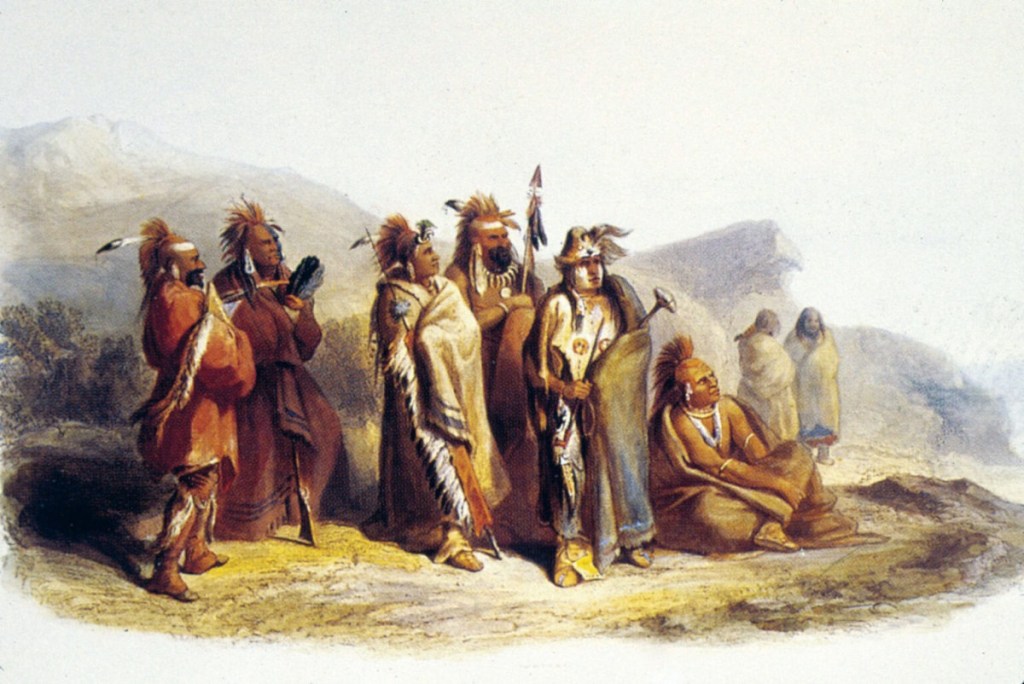

Sketch by George Catlin

The End of the Story and The Birth of a Legacy

Along the way, the prisoners would be greeted by huge crowds and lauded individuals like writer Washington Irving, and the artist, George Catlin, who sketched the men and portrayed them as instructed… in their chains.¹ They would meet with then President Andrew Jackson and be taken on a tour that included Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York before journeying further west over the Erie Canal and into the Great Lakes region. Black Hawk would recount his life story while imprisoned at Fort Armstrong, leaving behind his version of the events that shaped his life, as shared with Antoine LeClair, a mixed-race interpreter, and later translated for publication by J. P. Patterson, a newspaper editor. The autobiography is authentic and subjective, how could it not be? As for reliability, it is only as reliable as its translation and the intent of its translators allows. Regardless, it is a fascinating read.

Black Hawk was released from prison in 1833. He spent the rest of his life living quietly in Iowa amongst his people, where he was admired by his neighboring settlers, and often invited to attend legislative hearings at the territorial capital. Black’s last public appearance would take place on July 4, 1837. A year later, he gave a speech in which he conceded, “I thank the Great Spirit that I am now friendly with my white brethren”.

Black Hawk died on October 3, 1838, and was buried on the banks of the Des Moines River. Buried in full military uniform, a gift from General Jackson during a visit to Washington D.C., an American flag was raised at the head of his burial plot. Black Hawk’s story on the other hand, will live forever.

Sources:

¹ Special note: I was unable to find even one sketch portraying Black Hawk in chains.

blackhawkpark.org

digital.lib.niu.edu

wisconsinhistory.org

Autobiography of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, or Black Hawk

britannica.com

Leave a comment